I had been in Hobart, Tasmania, off Australia’s southern coast, for nearly two months on my first, and almost certainly my last, sabbatical. I had seen wombats, echidna, kookaburra, regularly heard the calls of forest ravens and cockatoos, and had visited a handful of local brewing establishments. And, yes, I had also been at work. This included taking baby steps in learning statistical computing and graphics (R programming) and a set of mathematical modeling principles (structural equation modeling). Along the way I had become a fan of Sewall Wright, a population geneticist who had famously studied guinea pigs, and I had created a two-color correlation graph with actual data that I had proudly shared with my adult children.

The goal of my sabbatical was to use these tools to understand a novel process by which a cat’s immune system could resist infection with feline immunodeficiency virus, or FIV. I hoped my findings would not only lead to new treatment options for cats with this disease, but, by analogy, guide novel ways to modify infections caused by the human disease correlate, HIV. This One Health project – linking animal disease to its human analogue – could push my laboratory studies in a new direction.

But on March 12, I received an unexpected notification from the U.S. Department of State advising “all current U.S. Fulbright participants to make arrangements to depart their country of assignment as soon as possible.”

Despite the growing pandemic pandemonium I had watched unfolding in news reports, it had not dawned on me that I might need to truncate my visit to the University of Tasmania, Australia, more than a month early. At that point, the small island state had very few confirmed cases of COVID-19 compared to countries coping with mounting catastrophe.

I had been poised to travel the next week to the University of Queensland and University of Sydney to visit veterinary colleagues working in the field of viral spillover and infectious disease. I was looking forward to meeting with Edward Holmes, a virologist at the scientific center of the growing pandemic, who for years has predicted events that could lead to a global disease outbreak. I was intending to ask Dr. Holmes about the practice and applications of One Health, the study of systemic problems that incorporate environmental, human, and animal considerations, using transdisciplinary approaches. The thoughts of this world expert on one of the most high-profile One Health topics – transmission of microbes from animals to humans when the environmental context favors rare events – would be of great assistance when I returned to Fort Collins at the end of my sabbatical to assume the role of director of the CSU One Health Institute. Yet, my visit was canceled by the most severe One Health crisis of our lifetime.

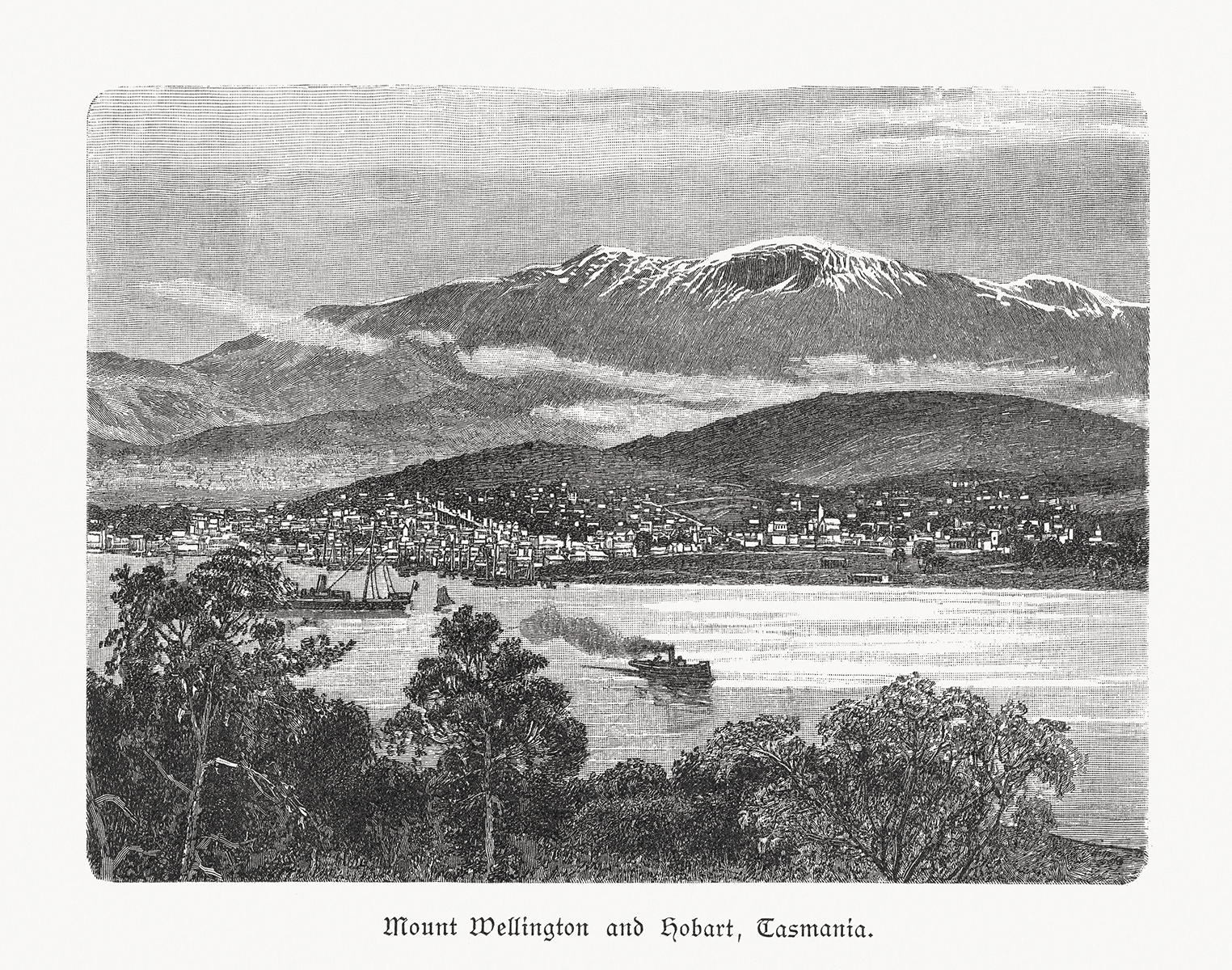

After receiving the State Department’s notice, I wrestled with the decision of whether to ride out the pandemic in a secluded spot about 3,600 miles north of Antarctica or endure a 30-plus hour trip through at least four airports during the exponential phase of SARS-CoV-2 spread. While considering my options, I biked and hiked along the River Derwent. Signs of the pandemic were virtually absent, other than hand sanitizer and social distancing behavior at the café. Flora and fauna were reassuringly untouched by the spasm gripping the human world, and this added surreal features to the circumstances. Communications with family, interspersed with final trips to Hill Street Grocery and other favorite haunts, helped me realize I needed to wrap up my trip. This decision was punctuated by announcements that Australia’s two primary airlines would be suspending all international flights. So with great inner sadness, I boarded a plane the next week in Hobart, and 30 hours later found myself back in Fort Collins.

The procedures in place at international terminals to intensify screening for COVID-19 consisted of collapsing each planeload of passengers into a small hallway to be asked individually if we had recently visited China. Given the number of passengers congregating through the small passageway – many of whom were wearing masks, some stifling coughs and sneezes – I spent my first two weeks in Fort Collins in self-isolation before transitioning home.

How does it feel to be here? Nothing is the same, and everything is the same. It is spring, the house is dusty, birds are deep in preening activities. Vistas of Pacific bays and stands of eucalyptus are replaced with prairie and foothills and old cottonwoods. I can’t stop thinking about how extraordinarily lucky I am.

I have become immersed in COVID-19 research activities and preparations to advance the CSU One Health Institute as a powerhouse. I am convinced CSU can be an absolute leader in this area; we have a remarkable coalition of passionate faculty who thrive on rolling up their sleeves, being practical, and working together.

Yesterday, for the first time in weeks, I looked at a spreadsheet and prepared to import it into R studio. I thought about standard equation modeling. I listened to the boreal chorus frogs and spotted a great horned owl. I reviewed the latest scientific findings about COVID-19 on bioRxiv and counted my blessings for living in a safe and secure environment. I realized it is time for One Health.

Sue VandeWoude, D.V.M., is a newly named University Distinguished Professor, the highest academic honor CSU awards to faculty for outstanding scholarship and achievement. She is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and a professor of comparative medicine whose research examines the ecology of infectious disease in wild and domestic cats, often using insights from feline disease to better understand equivalent diseases in people. VandeWoude recently transitioned from associate dean for research in the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences to director of the CSU One Health Institute.