It was 1901, and Dr. George Glover was irked. The young veterinarian had tested the college dairy herd for Mycobacterium bovis, the pathogen that causes bovine tuberculosis, and had discovered prevalent disease.

Glover, founder of Colorado State University’s world-class veterinary program, was sure that culling infected cattle from the campus herd – and from dairy herds everywhere – would prevent terrible human illness. At the time, tuberculosis nearly matched pneumonia as the leading cause of death in the United States; transmission of TB from cattle to people was a serious threat. To control contagion, the National Tuberculosis Eradication Program instituted widespread herd culling in 1917.

But convincing people before then? Just try.

“We urge upon all the warning that the difference between human and bovine tuberculosis has not yet been settled finally, and that the precautionary measures for preventing the spread of the disease by butter and milk cannot be safely abandoned,” Glover wrote in an Agricultural Experiment Station bulletin published in September 1901. He did not shy from fist shaking: “The conclusions arrived at by reliable authorities are here compiled, hoping to accomplish something toward arousing the masses from their lethargy.”

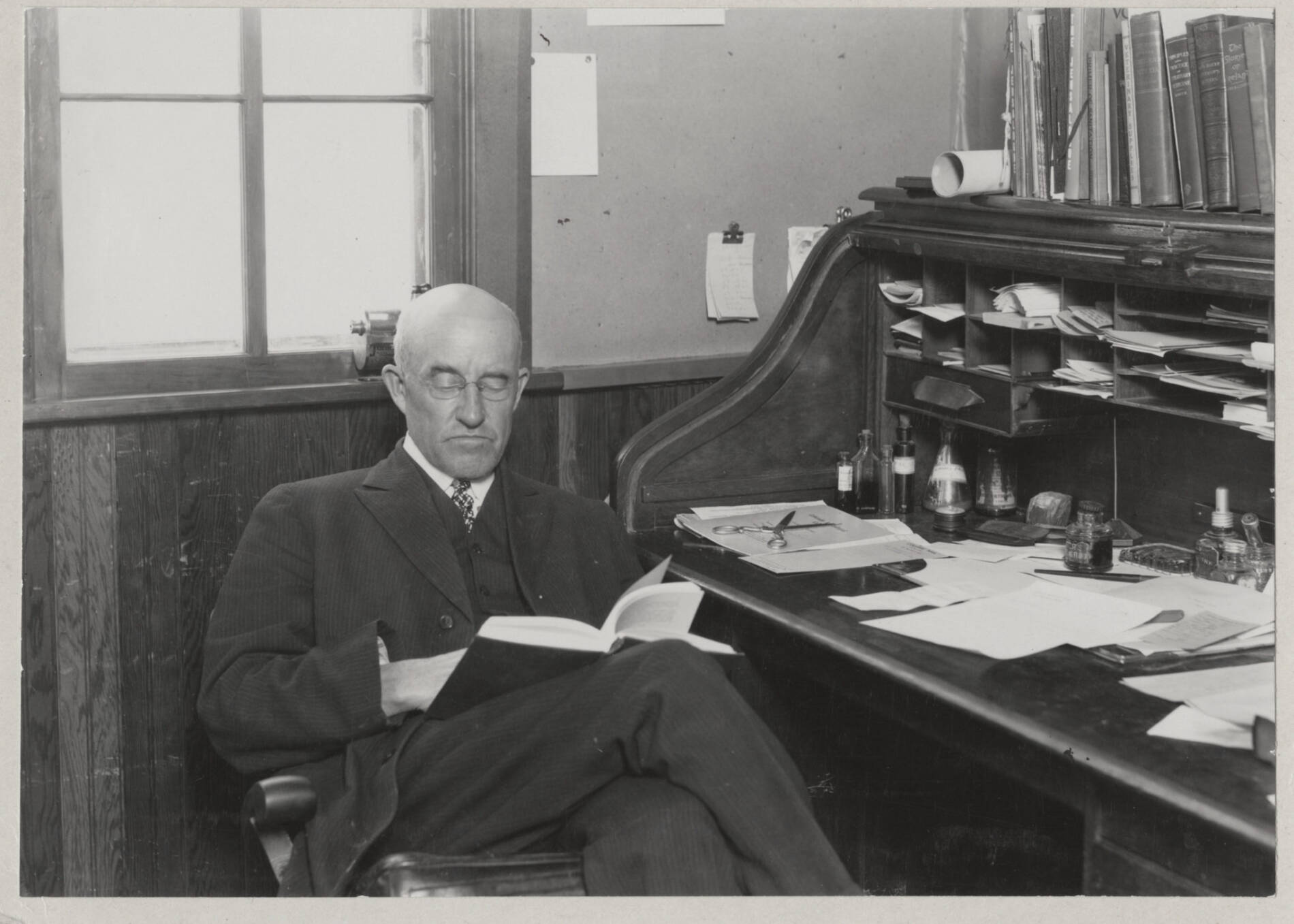

A farm kid from Longmont, Colorado, Glover arrived at the State Agricultural College of Colorado in his family’s lumber wagon in 1880, a year after the college opened. He was one of three students in the first graduating class in 1884 and co-founded the college Alumni Association. Glover attended veterinary school at Iowa Agricultural College, practiced for a time in Denver, and returned to Fort Collins to start the standout veterinary school here.

He started more than that: Glover initiated infectious disease research, a premier enterprise at the college that became Colorado State University. With his work on bovine tuberculosis, Glover was a vocal early proponent of a field later called One Health, whose practitioners pursue solutions to challenges involving people, animals, and the natural environment. Zoonotic diseases, which cross species, vividly illustrate the ties. Exhibit 1: COVID-19.

Glover knew veterinarians were perfectly positioned to improve public health. Who better to pinpoint the path of infectious disease from animals to people – and to seek cures for both?

The veterinarian also was forerunner of a CSU program of world renown: the Mycobacteria Research Laboratories. Founded in the 1980s, it is the largest academic research group in the United States dedicated to understanding and seeking cures for mycobacterial diseases, including tuberculosis and leprosy. These intractable infectious diseases remain devastating among people around the world.

The affiliation might be surprising, but it’s all of a piece. Starting in the late 1800s, Colorado was “the world’s sanatorium,” where countless consumptive patients sought relief from respiratory illness in clean, dry air and sunshine. The afflicted convalesced in tent cities and TB wards. Some of those facilities became hospitals, including National Jewish Health of Denver, a world leader in respiratory health.

At the college in Fort Collins, Glover was well aware of the scourge. It wasn’t so long after German physician and microbiologist Robert Koch discovered the tuberculosis bacterium and linked it to human disease; he later won the Nobel Prize for his discoveries. Science was still connecting other dots: that human and bovine forms of TB are related and spread among species, including wildlife; that tainted dairy products are a source of TB in people; that pasteurization kills infectious microorganisms in milk; and that prevention is the first line of defense in public health.

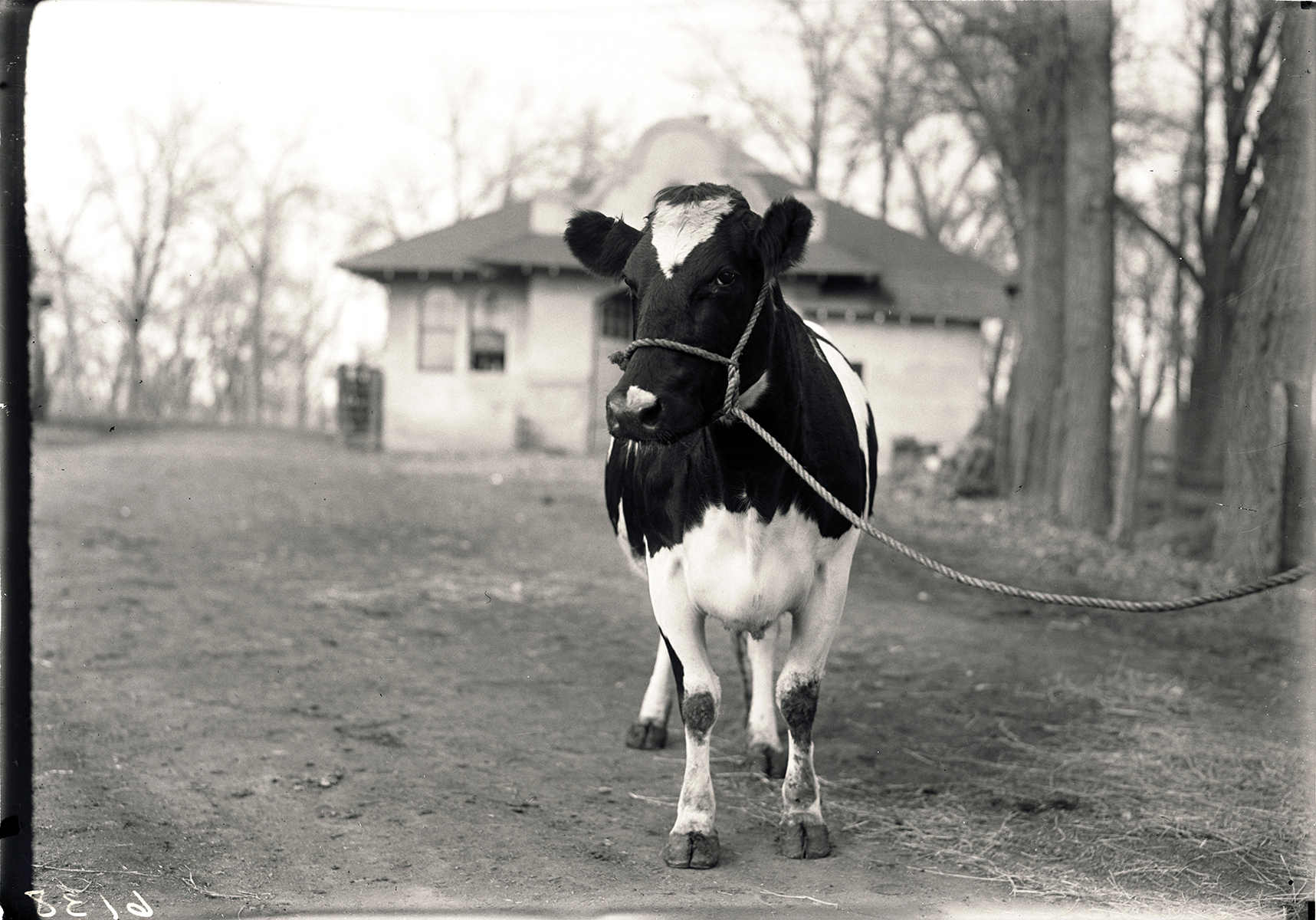

In 1901, Glover decided to prove the threat of bovine tuberculosis with a demonstration for the State Board of Agriculture, the college governing board. Members earlier had shown “scant tolerance” for Glover’s warnings. From the school’s dairy herd, the veterinarian picked a seemingly healthy cow, euthanized the animal, and performed a necropsy for the influential onlookers. The animal’s lungs and glands “were rotten with disease,” Glover recounted in 1944, during an interview with Ruth Wattles, an English professor who wrote a history of the university’s early years, titled The Mile High College.

As the book relates, Glover found a nodule of infection in the cow’s udder, removed it, and with a flourish, cut through it. “Out ran pus and milk on the ground,” Glover told Wattles.

“Dr. Glover stepped back dramatically and pointed. ‘That’s what you’ve been selling to people for milk,’” he declared, according to the historical account.

“An old-time cattleman and member of the board looked, spat, and cursed like a Missouri muleskinner. ‘I order this mess be cleaned up,’” he said, according to Glover’s retelling in The Mile High College.

With that, Glover had the go-ahead to cull tubercular dairy cows from the college herd and, in so doing, establish and promote scientifically valid practices for controlling bovine tuberculosis on farms and ranches across Colorado. The strategy gained traction. The nationwide campaign that began several years later – combined with commercial milk pasteurization and federal meat inspections – virtually eradicated bovine tuberculosis in the United States. It is heralded as a public health triumph.

Meantime, the human variant of TB, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has dramatically declined as a cause of illness and death in the United States.

Even so, an estimated 13 million people in the country are infected with a latent form of the disease without showing symptoms, representing a sleeping giant of potential illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Worldwide, TB remains a leading cause of death, infecting a staggering one-third of the global population and killing up to 2 million people annually, the World Health Organization reports.

CSU is seeking cures through its Mycobacteria Research Laboratories, an internationally respected research group investigating tuberculosis and other mycobacterial diseases.

The university’s modern era of TB research began in 1980, with the arrival of a rising biochemist named Patrick Brennan, a specialist in leprosy who had been a senior researcher at National Jewish Health of Denver. Brennan, a University Distinguished Professor Emeritus, served as chairman of the WHO Program for Tropical Disease Research, among other eminent roles.

In 1986, a key partner arrived: Ian Orme, a leading tuberculosis immunologist and one-of-a-kind educator and researcher. Together, Brennan and Orme – well-known as an Irishman and an Englishman – formally established the Mycobacteria Research Laboratories. They built the team into an international brain trust, with a stream of significant TB discoveries, from fundamental findings to vaccine and drug development. Orme, also a University Distinguished Professor, died in 2018.

The research group continues robust investigations through the work of 19 key faculty members and dozens of research staff and students.

“We have research that goes from basic science to preclinical work, testing drugs and vaccines,” said Dean Crick, a professor and director of the Mycobacteria Research Laboratories. “The breadth of the expertise is remarkable.”